Expert Says Cloudcroft Must Fix Aging Wastewater Plant as State Tightens Nitrogen Rules

With no current discharge permit, village officials are weighing high-dollar treatment upgrades while seeking to lease or buy the U.S. Forest Service land under the plant with looming deadlines.

Cloudcroft faces two big wastewater decisions at once:

How to upgrade an aging treatment plant to comply with new nitrogen limits, and

How to secure the federal land the plant sits on so that the village can make long-term investments in the location.

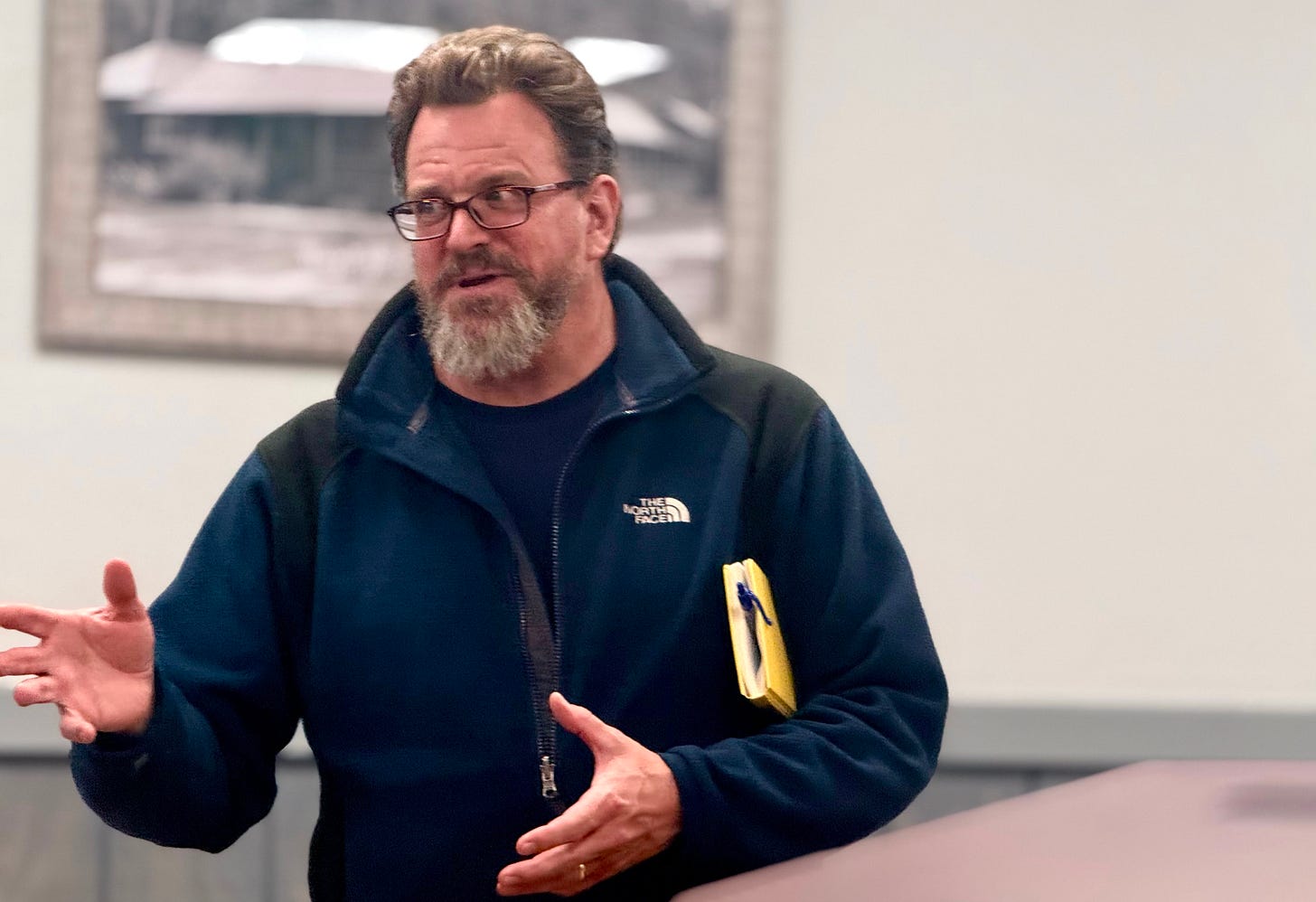

To get a handle on the challenges, the village met on Wednesday for a workshop presentation by technical assistance provider Robert George, following his tour of the wastewater treatment plant.

Robert George is a technical assistance provider and trainer who works with wastewater facilities across New Mexico. He has over 30 years of experience and assists facility operators, owners, city councils, and utility directors in ensuring compliance with discharge permits. His company, Oso del Agua, is contracted by the New Mexico Environment Department (NMED) Ground Water Quality Bureau.

George held an informative Q&A with the new leaders who will be tasked with getting the plant up to speed for permitting and securing land use for the village including Mayor Tim King and Trustees Jim Maynard, Gail McCoy, and Keith Hamilton, Public Works Supervisor Joe John “J.J.” Carrizal, longtime wastewater operator Scott Powell, Mayor‑elect Dusty Wiley, and Trustee‑elect Danny Hardwick.

State: No permit, strict limits coming

George started off by reminding officials that Cloudcroft’s wastewater plant is currently operating “without any permits,” which he called “pretty unusual” for a facility its size.

George said the state’s draft groundwater discharge permit proposes a total nitrogen limit of 10 milligrams per liter, and that “it became very obvious that the town cannot comply with that limit” with the existing configuration.

He expects the state to issue a redrafted permit with a compliance schedule that acknowledges “we know you can’t comply now, but we want you to come into compliance within a reasonable time frame,” likely over 3 to 5 years.

He also warned that as New Mexico takes over the federal surface‑water program, “there’s a fair to better than fair chance that the Village of Cloudcroft will be required to obtain a surface water discharge permit” on top of the groundwater permit.

Split system, tight nitrogen target

George described the plant as “straddling two worlds,” with some wastewater flowing through a newer membrane bioreactor (MBR) and “a good portion of it going through the ancient trickling filter.”

He said the older trickling‑filter plant, now pushing 70 years, still gives “remarkably good treatment” for organics and solids but does not remove nitrogen to the levels the draft permit would require.

George said that nitrogen levels leaving the plant must be reduced to 10 mg/L — and that the village’s treated water was “five times the limit, roughly.”

Why nitrogen is the focus

Nitrogen regulation protects drinking water quality and public health. Excess nitrate in groundwater can contaminate wells and cause serious health problems, particularly for infants and pregnant women. The state’s 10 mg/L limit aims to prevent wastewater discharge from raising nitrate levels in Cloudcroft’s aquifer above safe drinking water standards.

When trustees asked what soil does with nitrogen, George explained that bacteria in the unsaturated zone “are simply going to change it, change the form from ammonia to nitrate, and nitrate, once you form it up, [is] very mobile; it’s going to go where the water goes.” That nitrate can move into drinking‑water aquifers depending on local geology and groundwater flow.

Nitrogen sampling would typically be quarterly for a groundwater permit, he said, with the possibility of more frequent monitoring if a surface‑water permit is added later.

Tested water is from the combined filtration systems: both the newer MBRs and the trickling filter.

Data from 2023–24 showed the MBR delivering total nitrogen “under 10” mg/L when properly tuned, though Powell said recent MBR readings had been “bouncing between 10 and 15, 16 milligrams.”

Right now, George said, Powell is “pushing about 20 to 30,000 gallons a day through the MBR, and everything else is just sort of automatically shunted through the other treatment system.”

According to Public Works, the plant processes between 40,000 and nearly 230,000 gallons daily, depending on Cloudcroft’s population during peak tourist season.

As a near‑term experiment, George plans to recommend in his written report that the village route all flows through the MBR during low‑flow winter months, “mothballing the old plant,” and then bring it back online as seasonal demand rises. “We don’t know what the full effect of that is going to be,” he cautioned, and “we’re probably not going to be able to achieve compliance with what the permit would require,” but it could help the village “get the most out of the MBR treatment system” while a longer‑term fix is designed.

Engineering roadmap: PER before picking a fix

George repeatedly stressed that before the village commits to an upgrade path, it needs a full Preliminary Engineering Report (PER) focused on wastewater.

He said a PER lays out “the range of wastewater problems we’ve got to solve, here’s the options we could apply to it to solve it, here’s what the estimated costs are for each of those options.”

He said he had not seen evidence that earlier engineering work rose to the level of a comprehensive PER and that “it’s going to benefit you that you go down that path,” whether with CDM Smith or another firm.

CDM Smith engineers have already discussed bringing in package‑plant systems — factory‑built membrane units that, as the firm told the council in April, could “refresh the entire system for 30 to 50 years” at a cost similar to refurbishing the current setup, in the range of roughly $5.5 million to $7 million or more. George said the approach would increase MBR capacity by adding new cassettes and using existing basins.

Retired engineer and village resident John Snook proposed that adding new MBR cassettes could offer a smoother transition: “You can install them, hook them up, test them, and then cut it over before you ever have to do anything. That’s why the cassettes make more sense.”

When asked about specific options, George urged officials to study a “whole range of options,” not just more membrane cassettes.

He named Sequential Batch Reactors (SBRs) as “another reasonable solution” that can handle variable flows and achieve biological nitrogen removal using gravity clarifiers rather than membrane modules, which cost $100,000 to replace.

Aging plant, tight site

George said the old trickling‑filter plant remains critical backup infrastructure even as “the clock is just winding down on that thing.” Its secondary clarifier and filter are in poor condition, he said, but “thank goodness we have it” because it still provides “some level of treatment” and serves as a solids‑handling basin for the newer MBR.

If the village chose an SBR or a major reconfiguration, George said the new basin would “basically have to be built right on top of where the trickling filter and the other structures are,” which would mean “months and months of bypass, discharging pretty poorly treated wastewater, only partially treated wastewater” during construction.

He said that with conventional activated‑sludge basins, where concrete can last 30 to 40 years, and mechanical parts are replaced incrementally.

Earlier this year, CDM Smith Project Engineer Chad Johnson told the council that the MBR concrete basins are about 20 years old and that because “these had some problems in the beginning, their design life is less, so they could already be 50 percent or more through the design life.”

Land under the plant: lease, permit, or buy

Alongside the technical discussion, officials acknowledged that the plant itself sits on U.S. Forest Service land under special‑use authorization rather than on village‑owned property.

The plant sits on Forest Service property without a lease, permit, or ownership agreement.

Because the site is federal land and the plant is currently operating without a discharge permit, any long‑term upgrade plan will require the village to either secure a long‑term lease or negotiate the purchase of the footprint so that new investment, permitting, and financing can move forward on stable legal ground.

Mayor King told the Reader he met with forest officials earlier in the year, but the conversation made no headway. Trustee Maynard said the former land-use permit was not renewed and that past village communication with the Forest Service has been inconsistent and has yet to yield any results.

That land question ties directly into construction options.

If the village chooses an SBR or package plant that needs new basins, it will have to work within federal land constraints and any conditions attached to a Forest Service lease. If it pursues additional MBR cassettes within the existing basins, it must still demonstrate to regulators and funders that it has clear rights to operate and maintain the facility on that site over the life of the new equipment.

Staffing, pay, and succession

George devoted part of the workshop to village employees.

“I wanted to mention your staffing, and I’m happy to see that you have two Level 4 operators here,” he said. He noted he has known Powell for “30 years plus” and that “he’s probably getting pretty close to retirement,” urging the village to “figure out who his successor is going to be…and let him do his best to train that person” while Powell is still on staff.

“It’s very, very hard to find replacements” for highly licensed operators, George said, adding that many communities he visits have no licensed operators at all. Cloudcroft will likely “have to grow your own” future chief operator, he said, and he pointed out that having Carrizal as another Level 4 operator means “coverage for certification while the trainee becomes licensed.”

Those comments come after months of debate over pay in the Water and Wastewater Department.

On July 29, the council unanimously voted for 15 to 30 percent raises for four water and public works employees. Days later, Mayor King and Trustee McCoy publicly reconsidered their support, citing budget uncertainty, and in September, Mayor King said the July vote violated the Open Meetings Act because the item had been listed as a presentation. Village Attorney Zach Cook agreed.

On Oct. 6, after Trustees Maynard and Hamilton called a special meeting, where the Trustees voted 2-1 to officially approve the promised raises for Carrizal, Powell, and water operators Sean O’Connor and Kris Parks. Trustee McCoy dissented.

How does this fit into the PURe era and funding

Wednesday’s discussion builds on years of work around the PURe Water Project, launched in 2007 to turn treated wastewater into drinking water through direct potable reuse. In 2020, the New Mexico Environment Department denied a key PURe approval, citing the village’s failure to demonstrate sufficient treatment, management, and financial capacity.

The council then commissioned a system‑wide Preliminary Engineering Report from CDM Smith. Completed and unanimously approved in 2024, the PER recommended upgrading the wastewater plant, reducing non‑revenue water, and modernizing meters before any significant direct potable reuse investment.

George advised that direct potable reuse was a risky system without environmental safeguards. Environmental barriers give time to detect and respond if something goes wrong during treatment, rather than sending water straight back to the taps. Also, it provides additional natural treatment (filtration, mixing, biological processes) in the aquifer or soil.

He said that from an operator’s perspective, direct potable reuse is a “real operational challenge” and a natural barrier gives “a grace period between, oh, we detected a problem, and oh, this is going to be in our well next week.”

Everything at once, on the clock

The village now faces a linked set of challenges, and each makes the others harder.

No permit, strict limits. The plant has operated without an active discharge permit since the EPA withdrew federal authorization in 2017. The state’s draft groundwater permit, stalled since March 2024, would impose a 10 mg/L nitrogen limit. That requires a fivefold reduction from current levels, 50 to 60 mg/L at the influent.

Aging infrastructure. The 70-year-old trickling filter removes no nitrogen and struggles with summer peak flows. Officials must choose between adding MBR cassettes, building an SBR, or pursuing another fix. The clock is running on everything: the trickling filter, the MBR basins, the membrane cassettes.

No land rights. The plant sits on Forest Service property without a lease, permit, or ownership agreement. No lender or state regulator will fund major upgrades on land the village doesn’t control.

Millions needed. Whatever design the village picks will cost between $5.5 million and $7 million, or more. That money must come from grants, loans, bonds, and local revenue—assembled without breaking rate payers or sacrificing other village services.

Operator retirement looming. Scott Powell, a Level 4 operator with 30-plus years at the plant, is nearing retirement. Finding and training his replacement takes years, not months.

The bottom line: Cloudcroft needs a wastewater PER to pick a design, federal land tenure to build on, millions in funding to pay for it, and a trained operator to run it—all on a three-to-five-year compliance timeline that started when the state drafted that permit.

The Reader is proud to be sponsored in part by John R. Battle, CPA, CVA, MAFF, MCAA:

Promote Your Business

Learn about sponsorship opportunities for your business in support of the Reader. Contact us for more information at sponsorship-info@cloudcroftreader.com

Cloudcroft Reader is proud to be sponsored in part by great companies like:

Be in the Mountains Yoga & Massage

A cozy space for yoga and massage therapy at the Village PlazaOsha Trail Depot

Your destination for unique, hand-crafted treasuresCloudcroft Sandwich Shop

In the heart of downtown Cloudcroft, New MexicoJohn R. Battle, CPA, CVA, MAFF, CMAA

Personal & Business Taxes, Tax Planning & ConsultingThe Stove and Spa Store

We offer a variety of services to ensure your hearth and spa dreams are met!The Lodge at Cloudcroft

Landmark Choice Among New Mexico ResortsSacramento Camp & Conference Center

Come to the Mountain — Let God Refresh Your SoulNew Mexico Rails-to-Trails Association

We Convert Abandoned Railroad Lines Into Recreational TrailsLaughing Leaf Dispensary

Discover a world of wellness at Laughing LeafInstant Karma

Adventure Within: Transformative Yoga, Ayurvedic Wisdom, Nourishing Organics, Fair Trade BoutiqueOff the Beaten Path

Eclectic gifts & original artworkFuture Real Estate

Raise your expectations.Ski Cloudcroft

The southernmost ski area in New MexicoCloudcroft Therapeutic Massage

Maximizing Movement, Quality of Life ImprovementHigh Altitude

Your favorite little outdoor outfitter on Burro AvenueBlushing Yucca Esthetics

✨ Book your glow-up today✨The Elk Shed

Purveyors of Southwest Mountain Goods & FineryThe PAC

Pickleball Addicts of Cloudcroft—Pickleball in the CloudsPeñasco Valley Telephone Cooperative

For all the ways you love to connectBre Hope Media

Professional photo and video services

The Cloudcroft Reader is the most widely read publication serving the greater Cloudcroft community, with over 3,100 email subscribers and more than 13,900 Facebook followers. We do the reporting that no one else does.

Reach the people engaged with Cloudcroft — locals, seasonals, and visitors. Position your business just one click away.

Cloudcroft Stars make local news.

Thank you for supporting independent, factual, and fair coverage.

Thanks for reading. Subscribe for free articles and newsletters just like this, direct to your inbox.

This is a well written and informative article.